Red blood cell

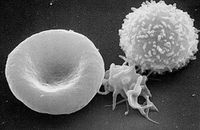

Red blood cells (also referred to as erythrocytes) are the most common type of blood cell and the vertebrate organism's principal means of delivering oxygen (O2) to the body tissues via the blood flow through the circulatory system. They take up oxygen in the lungs or gills and release it while squeezing through the body's capillaries.

These cells' cytoplasm is rich in hemoglobin, an iron-containing biomolecule that can bind oxygen and is responsible for the blood's red color.

In humans, mature red blood cells are flexible biconcave disks that lack a cell nucleus and most organelles. 2.4 million new erythrocytes are produced per second.[1] The cells develop in the bone marrow and circulate for about 100–120 days in the body before their components are recycled by macrophages. Each circulation takes about 20 seconds. Approximately a quarter of the cells in the human body are red blood cells.[2][3]

Red blood cells are also known as RBCs, red blood corpuscles (an archaic term), haematids, erythroid cells or erythrocytes (from Greek erythros for "red" and kytos for "hollow", with cyte translated as "cell" in modern usage). The capitalized term Red Blood Cells is the proper name in the US for erythrocytes in storage solution used in transfusion medicine.[4]

Contents |

History

The first person to describe red blood cells was the young Dutch biologist Jan Swammerdam, who had used an early microscope in 1658 to study the blood of a frog.[5] Unaware of this work, Anton van Leeuwenhoek provided another microscopic description in 1674, this time providing a more precise description of red blood cells, even approximating their size, "25,000 times smaller than a fine grain of sand".

In 1901 Karl Landsteiner published his discovery of the three main blood groups—A, B, and C (which he later renamed to O). Landsteiner described the regular patterns in which reactions occurred when serum was mixed with red blood cells, thus identifying compatible and conflicting combinations between these blood groups. A year later Alfred von Decastello and Adriano Sturli, two colleagues of Landsteiner, identified a fourth blood group—AB.

In 1959, by use of X-ray crystallography, Dr. Max Perutz was able to unravel the structure of hemoglobin, the red blood cell protein that carries oxygen.[6]

Vertebrate erythrocytes

Erythrocytes consist mainly of hemoglobin, a complex metalloprotein containing heme groups whose iron atoms temporarily bind to oxygen molecules (O2) in the lungs or gills and release them throughout the body. Oxygen can easily diffuse through the red blood cell's cell membrane. Hemoglobin in the erythrocytes also carries some of the waste product carbon dioxide back from the tissues; most waste carbon dioxide, however, is transported back to the pulmonary capillaries of the lungs as bicarbonate (HCO3-) dissolved in the blood plasma. Myoglobin, a compound related to hemoglobin, acts to store oxygen in muscle cells.[8]

The color of erythrocytes is due to the heme group of hemoglobin. The blood plasma alone is straw-colored, but the red blood cells change color depending on the state of the hemoglobin: when combined with oxygen the resulting oxyhemoglobin is scarlet, and when oxygen has been released the resulting deoxyhemoglobin is of a dark red burgundy color, appearing bluish through the vessel wall and skin. Pulse oximetry takes advantage of this color change to directly measure the arterial blood oxygen saturation using colorimetric techniques.

The sequestration of oxygen carrying proteins inside specialized cells (rather than having them dissolved in body fluid) was an important step in the evolution of vertebrates as it allows for less viscous blood, higher concentrations of oxygen, and better diffusion of oxygen from the blood to the tissues. The size of erythrocytes varies widely among vertebrate species; erythrocyte width is on average about 25% larger than capillary diameter and it has been hypothesized that this improves the oxygen transfer from erythrocytes to tissues.[9]

The only known vertebrates without erythrocytes are the crocodile icefishes (family Channichthyidae); they live in very oxygen rich cold water and transport oxygen freely dissolved in their blood.[10] While they don't use hemoglobin anymore, remnants of hemoglobin genes can be found in their genome.[11]

Nucleus

Erythrocytes in mammals are anucleate when mature, meaning that they lack a cell nucleus. In comparison, the erythrocytes of other vertebrates have nuclei; the only known exceptions are salamanders of the Batrachoseps genus and fish of the Maurolicus genus with closely related species.[12][13]

Secondary functions

When erythrocytes undergo shear stress in constricted vessels, they release ATP which causes the vessel walls to relax and dilate so as to promote normal blood flow.[14]

When their hemoglobin molecules are deoxygenated, erythrocytes release S-nitrosothiols which also acts to dilate vessels,[15] thus directing more blood to areas of the body depleted of oxygen.

It has been recently demonstrated that erythrocytes can also synthesize nitric oxide enzymatically, using L-arginine as substrate, just like endothelial cells.[16] Exposure of erythrocytes to physiological levels of shear stress activates nitric oxide synthase and export of nitric oxide,[17] which may contribute to the regulation of vascular tonus.

Erythrocytes can also produce hydrogen sulfide, a signalling gas that acts to relax vessel walls. It is believed that the cardioprotective effects of garlic are due to erythrocytes converting its sulfur compounds into hydrogen sulfide.[18]

Erythrocytes also play a part in the body's immune response: when lysed by pathogens such as bacteria, their hemoglobin releases free radicals which break down the pathogen's cell wall and membrane, killing it.[19][20]

Mammalian erythrocytes

Mammalian erythrocytes are unique among the vertebrates as they are non-nucleated cells in their mature form. These cells have nuclei during early phases of erythropoiesis, but extrude them during development as they mature in order to provide more space for hemoglobin. In mammals, erythrocytes also lose all other cellular organelles such as their mitochondria, golgi apparatus and endoplasmic reticulum. As a result of not containing mitochondria, these cells use none of the oxygen they transport; instead they produce the energy carrier ATP by lactic acid fermentation of glucose. Because of the lack of nuclei and organelles, mature red blood cells do not contain DNA and cannot synthesize any RNA, and consequently cannot divide and have limited repair capabilities.[21]

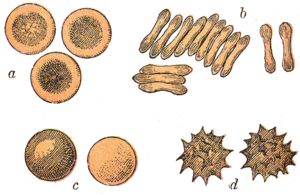

Mammalian erythrocytes are typically shaped as biconcave disks: flattened and depressed in the center, with a dumbbell-shaped cross section, and a torus-shaped rim on the edge of the disk. This distinctive biconcave shape optimises the flow properties of blood in the large vessels, such as maximization of laminar flow and minimization of platelet scatter, which suppresses their atherogenic activity in those large vessels.[22] However, there are some exceptions concerning shape in the artiodactyl order (even-toed ungulates including cattle, deer, and their relatives), which displays a wide variety of bizarre erythrocyte morphologies: small and highly ovaloid cells in llamas and camels (family Camelidae), tiny spherical cells in mouse deer (family Tragulidae), and cells which assume fusiform, lanceolate, crescentic, and irregularly polygonal and other angular forms in red deer and wapiti (family Cervidae). Members of this order have clearly evolved a mode of RBC development substantially different from the mammalian norm.[7][23] Overall, mammalian erythrocytes are remarkably flexible and deformable so as to squeeze through tiny capillaries, as well as to maximize their apposing surface by assuming a cigar shape, where they efficiently release their oxygen load.[24]

In large blood vessels, red blood cells sometimes occur as a stack, flat side next to flat side. This is known as rouleaux formation, and it occurs more often if the levels of certain serum proteins are elevated, as for instance during inflammation.

The spleen acts as a reservoir of red blood cells, but this effect is somewhat limited in humans. In some other mammals such as dogs and horses, the spleen sequesters large numbers of red blood cells which are dumped into the blood during times of exertion stress, yielding a higher oxygen transport capacity.

Human erythrocytes

A typical human erythrocyte has a disk diameter of 6–8 µm and a thickness of 2 µm, being much smaller than most other human cells. These cells have a volume of about 90 fL with a surface of about 136 μm2, and can swell up to a sphere shape containing 150 fL, without membrane distension.

Adult humans have roughly 2–3 × 1013 (20-30 trillion) red blood cells at any given time, comprising approximately one quarter of the total human body cell number (women have about 4 to 5 million erythrocytes per microliter (cubic millimeter) of blood and men about 5 to 6 million; people living at high altitudes with low oxygen tension will have more). Red blood cells are thus much more common than the other blood particles: there are about 4,000–11,000 white blood cells and about 150,000–400,000 platelets in each microliter of human blood.

Human red blood cells take on average 20 seconds to complete one cycle of circulation.[2][3][25] As red blood cells contain no nucleus, protein biosynthesis is currently assumed to be absent in these cells, although a recent study indicates the presence of all the necessary biomachinery in human red blood cells for protein biosynthesis.[21]

The blood's red color is due to the spectral properties of the hemic iron ions in hemoglobin. Each human red blood cell contains approximately 270 million of these hemoglobin biomolecules, each carrying four heme groups; hemoglobin comprises about a third of the total cell volume. This protein is responsible for the transport of more than 98% of the oxygen (the remaining oxygen is carried dissolved in the blood plasma). The red blood cells of an average adult human male store collectively about 2.5 grams of iron, representing about 65% of the total iron contained in the body.[26][27] (See Human iron metabolism.)

Life cycle

Human erythrocytes are produced through a process named erythropoiesis, developing from committed stem cells to mature erythrocytes in about 7 days. When matured, these cells live in blood circulation for about 100 to 120 days. At the end of their lifespan, they become senescent, and are removed from circulation.

Erythropoiesis

Erythropoiesis is the development process in which new erythrocytes are produced, through which each cell matures in about 7 days. Through this process erythrocytes are continuously produced in the red bone marrow of large bones, at a rate of about 2 million per second in a healthy adult. (In the embryo, the liver is the main site of red blood cell production.) The production can be stimulated by the hormone erythropoietin (EPO), synthesised by the kidney. Just before and after leaving the bone marrow, the developing cells are known as reticulocytes; these comprise about 1% of circulating red blood cells.

Functional lifetime

This phase lasts about 100–120 days, during which the erythrocytes are continually moving by the blood flow push (in arteries), pull (in veins) and squeezing through microvessels such as capillaries as they compress against each other in order to move.

Senescence

The aging erythrocyte undergoes changes in its plasma membrane, making it susceptible to selective recognition by macrophages and subsequent phagocytosis in the reticuloendothelial system (spleen, liver and bone marrow), thus removing old and defective cells and continually purging the blood. This process is termed eryptosis, or erythrocyte programmed cell death. This process normally occurs at the same rate of production by erythropoiesis, balancing the total circulating red blood cell count. Eryptosis is increased in a wide variety of diseases including sepsis, haemolytic uremic syndrome, malaria, sickle cell anemia, beta-thalassemia, glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase deficiency, phosphate depletion, iron deficiency and Wilson's disease. Eryptosis can be elicited by osmotic shock, oxidative stress, energy depletion as well as a wide variety of endogenous mediators and xenobiotics. Excessive eryptosis is observed in erythrocytes lacking the cGMP-dependent protein kinase type I or the AMP-activated protein kinase AMPK. Inhibitors of eryptosis include erythropoietin, nitric oxide, catecholamines and high concentrations of urea.

Much of the resulting important breakdown products are recirculated in the body. The heme constituent of hemoglobin are broken down into Fe3+ and biliverdin. The biliverdin is reduced to bilirubin, which is released into the plasma and recirculated to the liver bound to albumin. The iron is released into the plasma to be recirculated by a carrier protein called transferrin. Almost all erythrocytes are removed in this manner from the circulation before they are old enough to hemolyze. Hemolyzed hemoglobin is bound to a protein in plasma called haptoglobin which is not excreted by the kidney.[28]

Membrane composition

The membrane of the red blood cell plays many roles that aid in regulating their surface deformability, flexibility, adhesion to other cells and immune recognition. These functions are highly dependent on its composition, which defines its properties. The red blood cell membrane is composed of 3 layers: the glycocalyx on the exterior, which is rich in carbohydrates; the lipid bilayer which contains many transmembrane proteins, besides its lipidic main constituents; and the membrane skeleton, a structural network of proteins located on the inner surface of the lipid bilayer. In human erythrocytes, like in most mammal erythrocytes, half of the membrane mass is represented by proteins and the other half are lipids, namely phospholipids and cholesterol.[29]

Membrane lipids

The erythrocyte cell membrane comprises a typical lipid bilayer, similar to what can be found in virtually all human cells. Simply put, this lipid bilayer is composed of cholesterol and phospholipids in equal proportions by weight. The lipid composition is important as it defines many physical properties such as membrane permeability and fluidity. Additionally, the activity of many membrane proteins is regulated by interactions with lipids in the bilayer.

Unlike cholesterol which is evenly distributed between the inner and outer leaflets, the 5 major phospholipids are asymmetrically disposed, as shown below:

Outer monolayer

- Phosphatidylcholine (PC);

- Sphingomyelin (SM).

Inner monolayer

- Phosphatidylethanolamine (PE);

- Phosphoinositol (PI) (small amounts).

- Phosphatidylserine (PS);

This asymmetric phospholipid distribution among the bilayer is the result of the function of several energy-dependent and energy-independent phospholipid transport proteins. Proteins called “Flippases” move phospholipids from the outer to the inner monolayer while others called “floppases” do the opposite operation, against a concentration gradient in an energy dependent manner. Additionally, there are also “scramblase” proteins that move phospholipids in both directions at the same time, down their concentration gradients in an energy independent manner. There is still considerable debate ongoing regarding the identity of these membrane maintenance proteins in the red cell membrane.

The maintenance of an asymmetric phospholipid distribution in the bilayer (such as an exclusive localization of PS and PIs in the inner monolayer) is critical for the cell integrity and function due to several reasons:

- Macrophages recognize and phagocytose red cells that expose PS at their outer surface. Thus the confinement of PS in the inner monolayer is essential if the cell is to survive its frequent encounters with macrophages of the reticuloendothelial system, especially in the spleen.

- Premature destruction of thallassemic and sickle red cells has been linked to disruptions of lipid asymmetry leading to exposure of PS on the outer monolayer.

- An exposure of PS can potentiate adhesion of red cells to vascular endothelial cells, effectively preventing normal transit through the microvasculature. Thus it is important that PS is maintained only in the inner leaflet of the bilayer to ensure normal blood flow in microcirculation.

- Both PS and phosphatidylinositol-4,5-bisphosphate (PIP2) can regulate membrane mechanical function, due to their interactions with skeletal proteins such as spectrin and protein 4.1R. Recent studies have shown that binding of spectrin to PS promotes membrane mechanical stability. PIP2 enhances the binding of protein band 4.1R to glycophorin C but decreases its interaction with protein band 3, and thereby may modulate the linkage of the bilayer to the membrane skeleton.

The presence of specialized structures named "lipid rafts" in the erythrocyte membrane have been described by recent studies. These are structures enriched in cholesterol and sphingolipids associated with specific membrane proteins, namely flotillins, stomatins (band 7), G-proteins, and β-adrenergic receptors. Lipid rafts that have been implicated in cell signaling events in nonerythroid cells have been shown in erythroid cells to mediate β2-adregenic receptor signaling and increase cAMP levels, and thus regulating entry of malarial parasites into normal red cells.[30][31]

Membrane proteins

The proteins of the membrane skeleton are responsible for the deformability, flexibility and durability of the red blood cell, enabling it to squeeze through capillaries less than half the diameter of the erythrocyte (7-8 μm) and recovering the discoid shape as soon as these cells stop receiving compressive forces, in a similar fashion to an object made of rubber.

There are currently more than 50 known membrane proteins, which can exist in a few hundred up to a million copies per erythrocyte. Approximately 25 of these membrane proteins carry the various blood group antigens, such as the A, B and Rh antigens, among many others. These membrane proteins can perform a wide diversity of functions, such as transporting ions and molecules across the red cell membrane, adhesion and interaction with other cells such as endothelial cells, as signaling receptors, as well as other currently unknown functions. The blood types of humans are due to variations in surface glycoproteins of erythrocytes. Disorders of the proteins in these membranes are associated with many disorders, such as hereditary spherocytosis, hereditary elliptocytosis, hereditary stomatocytosis, and paroxysmal nocturnal hemoglobinuria.[29][30]

The red blood cell membrane proteins organized according to their function:

Transport

- Band 3 - Anion transporter, also an important structural component of the erythrocyte cell membrane, makes up to 25% of the cell membrane surface, each red cell contains approximately one million copies. Defines the Diego Blood Group;[33]

- Aquaporin 1 - water transporter, defines the Colton Blood Group;

- Glut1 - glucose and L-dehydroascorbic acid transporter;

- Kidd antigen protein - urea transporter;

- RhAG - gas transporter, probably of carbon dioxide, defines Rh Blood Group and the associated unusual blood group phenotype Rhnull;

- Na+/K+ - ATPase;

- Ca2+ - ATPase;

- Na+ K+ 2Cl- - cotransporter;

- Na+-Cl- - cotransporter;

- Na-H exchanger;

- K-Cl - cotransporter;

- Gardos Channel.

Cell adhesion

- ICAM-4 - interacts with integrins;

- BCAM - a glycoprotein that defines the Lutheran blood group and also known as Lu or laminin-binding protein.

Structural role - The following membrane proteins establish linkages with skeletal proteins and may play an important role in regulating cohesion between the lipid bilayer and membrane skeleton, likely enabling the red cell to maintain its favorable membrane surface area by preventing the membrane from collapsing (vesiculating).

- Ankyrin-based macromolecular complex - proteins linking the bilayer to the membrane skeleton through the interaction of their cytoplasmic domains with Ankyrin.

- Band 3 - also assembles various glycolytic enzymes, the presumptive CO2 transporter, and carbonic anhydrase into a macromolecular complex termed a “metabolon,” which may play a key role in regulating red cell metabolism and ion and gas transport function);

- RhAG - also involved in transport, defines associated unusual blood group phenotype Rhmod.

- Protein 4.1R-based macromolecular complex - proteins interacting with Protein 4.1R.

- Protein 4.1R - weak expression of Gerbich antigens;

- Glycophorin C and D - glycoprotein, defines Gerbich Blood Group;

- XK - defines the Kell Blood Group and the Mcleod unusual phenotype (lack of Kx antigen and greatly reduced expression of Kell antigens);

- RhD/RhCE - defines Rh Blood Group and the associated unusual blood group phenotype Rhnull;

- Duffy protein - has been proposed to be associated with chemokine clearance;[34]

- Adducin - interaction with band 3;

- Dematin- interaction with the Glut1 glucose transporter.

Separation and blood doping

Red blood cells can be obtained from whole blood by centrifugation, which separates the cells from the blood plasma. During plasma donation, the red blood cells are pumped back into the body right away and the plasma is collected. Some athletes have tried to improve their performance by blood doping: first about 1 litre of their blood is extracted, then the red blood cells are isolated, frozen and stored, to be reinjected shortly before the competition. (Red blood cells can be conserved for 5 weeks at −79 °C.) This practice is hard to detect but may endanger the human cardiovascular system which is not equipped to deal with blood of the resulting higher viscosity.

Artificially grown red blood cells

In 2008 it was reported that human embryonic stem cells had been successfully coaxed into becoming erythrocytes in the lab. The difficult step was to induce the cells to eject their nucleus; this was achieved by growing the cells on stromal cells from the bone marrow. It is hoped that these artificial erythrocytes can eventually be used for blood transfusions.[35]

Diseases and diagnostic tools

Blood diseases involving the red blood cells include:

- Anemias (or anaemias) are diseases characterized by low oxygen transport capacity of the blood, because of low red cell count or some abnormality of the red blood cells or the hemoglobin.

-

- Iron deficiency anemia is the most common anemia; it occurs when the dietary intake or absorption of iron is insufficient, and hemoglobin, which contains iron, cannot be formed

-

- Sickle-cell disease is a genetic disease that results in abnormal hemoglobin molecules. When these release their oxygen load in the tissues, they become insoluble, leading to mis-shaped red blood cells. These sickle shaped red cells are rigid and cause blood vessel blockage, pain, strokes, and other tissue damage.

-

- Thalassemia is a genetic disease that results in the production of an abnormal ratio of hemoglobin subunits.

-

- Spherocytosis is a genetic disease that causes a defect in the red blood cell's cytoskeleton, causing the red blood cells to be small, sphere-shaped, and fragile instead of donut-shaped and flexible.

-

- Pernicious anemia is an autoimmune disease wherein the body lacks intrinsic factor, required to absorb vitamin B12 from food. Vitamin B12 is needed for the production of hemoglobin.

-

- Aplastic anemia is caused by the inability of the bone marrow to produce blood cells.

-

- Pure red cell aplasia is caused by the inability of the bone marrow to produce only red blood cells.

- Hemolysis is the general term for excessive breakdown of red blood cells. It can have several causes and can result in hemolytic anemia.

-

- The malaria parasite spends part of its life-cycle in red blood cells, feeds on their hemoglobin and then breaks them apart, causing fever. Both sickle-cell disease and thalassemia are more common in malaria areas, because these mutations convey some protection against the parasite.

- Polycythemias (or erythrocytoses) are diseases characterized by a surplus of red blood cells. The increased viscosity of the blood can cause a number of symptoms.

-

- In polycythemia vera the increased number of red blood cells results from an abnormality in the bone marrow.

- Several microangiopathic diseases, including disseminated intravascular coagulation and thrombotic microangiopathies, present with pathognomonic (diagnostic) RBC fragments called schistocytes. These pathologies generate fibrin strands that sever RBCs as they try to move past a thrombus.

- Inherited hemolytic anemias caused by abnormalities of the erythrocyte membrane comprise an important group of inherited disorders. These disorders are characterized by clinical and biochemical heterogeneity and also genetic heterogeneity, as evidenced by recent molecular studies.

-

- The Hereditary spherocytosis (HS) syndromes are a group of inherited disorders characterized by the presence of spherical-shaped erythrocytes on the peripheral blood smear. HS is found worldwide. It is the most common inherited anemia in individuals of northern European descent, affecting approximately 1 in 1000-2500 individuals depending on the diagnostic criteria. The primary defect in hereditary spherocytosis is a deficiency of membrane surface area. Decreased surface area may produced by two different mechanisms: 1) Defects of spectrin, ankyrin, or protein 4.2 lead to reduced density of the membrane skeleton, destabilizing the overlying lipid bilayer and releasing band 3-containing microvesicles. 2) Defects of band 3 lead to band 3 deficiency and loss of its lipid-stabilizing effect. This results in the loss of band 3-free microvesicles. Both pathways result in membrane loss, decreased surface area, and formation of spherocytes with decreased deformability. These deformed erythrocytes become trapped in the hostile environment of the spleen where splenic conditioning inflicts further membrane damage, amplifying the cycle of membrane injury.

- Hereditary elliptocytosis

- Hereditary pyropoikilocytosis

- Hereditary stomatocytosis[36]

- Hemolytic transfusion reaction is the destruction of donated red blood cells after a transfusion, mediated by host antibodies, often as a result of a blood type mismatch.

Several blood tests involve red blood cells, including the RBC count (the number of red blood cells per volume of blood), the hematocrit (percentage of blood volume occupied by red blood cells), and the erythrocyte sedimentation rate. The blood type needs to be determined to prepare for a blood transfusion or an organ transplantation.

See also

- Hemoglobin-based oxygen carriers

- Packed red blood cells

- Blood serum

- Altitude training

References

- ↑ Erich Sackmann, Biological Membranes Architecture and Function., Handbook of Biological Physics, (ed. R.Lipowsky and E.Sackmann, vol.1, Elsevier, 1995

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Laura Dean. Blood Groups and Red Cell Antigens

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Pierigè F, Serafini S, Rossi L, Magnani M (January 2008). "Cell-based drug delivery". Advanced Drug Delivery Reviews 60 (2): 286–95. doi:10.1016/j.addr.2007.08.029. PMID 17997501.

- ↑ "Circular of Information for Blood and Blood Products" (pdf). American Association of Blood Banks, American Red Cross, America's Blood Centers. http://www.fda.gov/Cber/gdlns/crclr.pdf. Retrieved 2008-07-28.

- ↑ "Swammerdam, Jan (1637–1680)", McGraw Hill AccessScience, 2007. Accessed 27 December 2007.

- ↑ Red Gold - Blood History Timeline, PBS 2002. Accessed 27 December 2007.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Gulliver, G. (1875). "On the size and shape of red corpuscles of the blood of vertebrates, with drawings of them to a uniform scale, and extended and revised tables of measurements". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London 1875: 474–495.

- ↑ Maton, Anthea; Jean Hopkins, Charles William McLaughlin, Susan Johnson, Maryanna Quon Warner, David LaHart, Jill D. Wright (1993). Human Biology and Health. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey, USA: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-13-981176-1.

- ↑ Snyder, Gregory K.; Sheafor, Brandon A. (1999). "Red Blood Cells: Centerpiece in the Evolution of the Vertebrate Circulatory System". Integrative and Comparative Biology 39: 189. doi:10.1093/icb/39.2.189.

- ↑ Ruud JT (May 1954). "Vertebrates without erythrocytes and blood pigment". Nature 173 (4410): 848–50. doi:10.1038/173848a0. PMID 13165664.

- ↑ Carroll, Sean (2006). The Making of the Fittest. W.W. Norton. ISBN 0393061639.

- ↑ Cohen, W. D. (1982). "The cytomorphic system of anucleate non-mammalian erythrocytes". Protoplasma 113: 23. doi:10.1007/BF01283036.

- ↑ Wingstrand KG (1956). "Non-nucleated erythrocytes in a teleostean fish Maurolicus mülleri (Gmelin)". Zeitschrift Für Zellforschung Und Mikroskopische Anatomie 45 (2): 195–200. doi:10.1007/BF00338830 (inactive 2009-12-02). PMID 13402080. http://www.springerlink.com/content/j943833n74065634.

- ↑ Wan J, Ristenpart WD, Stone HA (October 2008). "Dynamics of shear-induced ATP release from red blood cells". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 105 (43): 16432–7. doi:10.1073/pnas.0805779105. PMID 18922780.

- ↑ Diesen DL, Hess DT, Stamler JS (August 2008). "Hypoxic vasodilation by red blood cells: evidence for an s-nitrosothiol-based signal". Circulation Research 103 (5): 545–53. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.108.176867. PMID 18658051.

- ↑ Kleinbongard P, Schutz R, Rassaf T, et al (2006). "Red blood cells express a functional endothelial nitric oxide synthase". Blood 107 (7): 2943–51. doi:10.1182/blood-2005-10-3992. PMID 16368881.

- ↑ Ulker P, Sati L, Celik-Ozenci C, Meiselman HJ, Baskurt OK (2009). "Mechanical stimulation of nitric oxide synthesizing mechanisms in erythrocytes". Biorheology 46 (2): 121–32. doi:10.3233/BIR-2009-0532. PMID 19458415.

- ↑ Benavides, Gloria A; Giuseppe L Squadrito, Robert W Mills, Hetal D Patel, T Scott Isbell, Rakesh P Patel, Victor M Darley-Usmar, Jeannette E Doeller, David W Kraus (2007-11-13). "Hydrogen sulfide mediates the vasoactivity of garlic". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 104 (46): 17977–17982. doi:10.1073/pnas.0705710104. PMID 17951430. PMC 2084282. http://www.pnas.org/content/104/46/17977.full. Retrieved 2010-03-03.

- ↑ Red blood cells do more than just carry oxygen. New findings by NUS team show they aggressively attack bacteria too., The Straits Times, 1 September 2007

- ↑ Jiang N, Tan NS, Ho B, Ding JL (October 2007). "Respiratory protein-generated reactive oxygen species as an antimicrobial strategy". Nature Immunology 8 (10): 1114–22. doi:10.1038/ni1501. PMID 17721536.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Kabanova S, Kleinbongard P, Volkmer J, Andrée B, Kelm M, Jax TW (2009). "Gene expression analysis of human red blood cells". International Journal of Medical Sciences 6 (4): 156–9. PMID 19421340. PMC 2677714. http://www.medsci.org/v06p0156.htm.

- ↑ Uzoigwe C (2006). "The human erythrocyte has developed the biconcave disc shape to optimise the flow properties of the blood in the large vessels". Medical Hypotheses 67 (5): 1159–63. doi:10.1016/j.mehy.2004.11.047. PMID 16797867.

- ↑ Gregory TR (2001). "The bigger the C-value, the larger the cell: genome size and red blood cell size in vertebrates". Blood Cells, Molecules & Diseases 27 (5): 830–43. doi:10.1006/bcmd.2001.0457. PMID 11783946.

- ↑ Goodman SR, Kurdia A, Ammann L, Kakhniashvili D, Daescu O (December 2007). "The human red blood cell proteome and interactome". Experimental Biology and Medicine 232 (11): 1391–408. doi:10.3181/0706-MR-156. PMID 18040063.

- ↑ Hillman, Robert S.; Ault, Kenneth A.; Rinder, Henry M. (2005). Hematology in Clinical Practice: A Guide to Diagnosis and Management (4 ed.). McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 1. ISBN 0071440356.

- ↑ Iron Metabolism, University of Virginia Pathology. Accessed 22 September 2007.

- ↑ Iron Transport and Cellular Uptake by Kenneth R. Bridges, Information Center for Sickle Cell and Thalassemic Disorders. Accessed 22 September 2007.

- ↑ Föller M, Huber SM, Lang F (October 2008). "Erythrocyte programmed cell death". IUBMB Life 60 (10): 661–8. doi:10.1002/iub.106. PMID 18720418.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Yazdanbakhsh K, Lomas-Francis C, Reid ME (October 2000). "Blood groups and diseases associated with inherited abnormalities of the red blood cell membrane". Transfusion Medicine Reviews 14 (4): 364–74. doi:10.1053/tmrv.2000.16232. PMID 11055079.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 Mohandas N, Gallagher PG (November 2008). "Red cell membrane: past, present, and future". Blood 112 (10): 3939–48. doi:10.1182/blood-2008-07-161166. PMID 18988878.

- ↑ Rodi PM, Trucco VM, Gennaro AM (June 2008). "Factors determining detergent resistance of erythrocyte membranes". Biophysical Chemistry 135 (1-3): 14–8. doi:10.1016/j.bpc.2008.02.015. PMID 18394774.

- ↑ Hempelmann E, Götze O (1984). "Characterization of membrane proteins by polychromatic silver staining". Hoppe Seyler's Z Physiol Chem 365: 241–242.

- ↑ Iolascon A, Perrotta S, Stewart GW (March 2003). "Red blood cell membrane defects". Reviews in Clinical and Experimental Hematology 7 (1): 22–56. PMID 14692233.

- ↑ Denomme GA (July 2004). "The structure and function of the molecules that carry human red blood cell and platelet antigens". Transfusion Medicine Reviews 18 (3): 203–31. doi:10.1016/j.tmrv.2004.03.006. PMID 15248170.

- ↑ First red blood cells grown in the lab, New Scientist News, 19 August 2008

- ↑ An X, Mohandas N (May 2008). "Disorders of red cell membrane". British Journal of Haematology 141 (3): 367–75. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2141.2008.07091.x. PMID 18341630.

External links

- Blood Groups and Red Cell Antigens by Laura Dean. Searchable and downloadable online textbook in the public domain.

- Database of vertebrate erythrocyte sizes.

- Red Gold, PBS site containing facts and history

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||